- Home

- John Harris

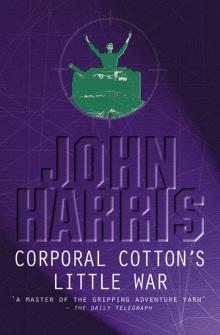

Corporal Cotton's Little War

Corporal Cotton's Little War Read online

Copyright & Information

Corporal Cotton’s Little War

First published in 1979

Copyright: Juliet Harris; House of Stratus 1979-2011

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

The right of John Harris to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

This edition published in 2011 by House of Stratus, an imprint of

Stratus Books Ltd., Lisandra House, Fore Street, Looe,

Cornwall, PL13 1AD, UK.

Typeset by House of Stratus.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library and the Library of Congress.

ISBN EAN Edition

075510241X 9780755102419 Print

0755127374 9780755127375 Mobi/Kindle

075512765X 9780755127658 Epub

This is a fictional work and all characters are drawn from the author’s imagination.

Any resemblance or similarities to persons either living or dead are entirely coincidental.

www.houseofstratus.com

About the Author

John Harris, wrote under his own name and also the pen names of Mark Hebden and Max Hennessy.

He was born in 1916 and educated at Rotherham Grammar School before becoming a journalist on the staff of the local paper. A short period freelancing preceded World War II, during which he served as a corporal attached to the South African Air Force. Moving to the Sheffield Telegraph after the war, he also became known as an accomplished writer and cartoonist. Other ‘part time’ careers followed.

He started writing novels in 1951 and in 1953 had considerable success when his best-selling The Sea Shall Not Have Them was filmed. He went on to write many more war and modern adventure novels under his own name, and also some authoritative non-fiction, such as Dunkirk. Using the name Max Hennessy, he wrote some very accomplished historical fiction and as Mark Hebden, the ‘Chief Inspector’ Pel novels which feature a quirky Burgundian policeman.

Harris was a sailor, an airman, a journalist, a travel courier, a cartoonist and a history teacher, who also managed to squeeze in over eighty books. A master of war and crime fiction, his enduring novels are versatile and entertaining.

Author’s Note

For the benefit of those who don’t know, perhaps it would be an advantage to explain what was happening in Europe in the spring of 1941, when this book begins. At that period of World War II, when Britain’s fortunes had reached their nadir and the German swastika fluttered confidently over the capitals of Europe, the Mediterranean suddenly blazed into action.

In late 1940, eager to emulate the German successes in France, Norway, Denmark and Holland and half-expecting it to fall into his lap like a ripe plum, Mussolini had attacked Greece from Albania, which he had occupied before the war. Immediately, the Greeks asked the British government to stand by a promise made in 1939 that Britain would go to their help in the event of invasion. Unfortunately, while this idea had been fine in 1939, in 1940, with the British in North Africa already conducting half a dozen campaigns at once, there were too many commitments elsewhere and, apart from a few dozen aircraft, a British mission and a token force of troops, there was precious little assistance Britain could afford to give.

Nevertheless, there was one big strategic prize to be snatched from under the noses of the Italian invaders. Crete, with its fine natural harbour of Suda Bay, afforded a valuable advanced fuelling base for naval operations in the central Mediterranean, and at the invitation of the Greek government it was occupied by British forces just three days after the Italian attack. As a result, Admiral Cunningham, C-in-C, Mediterranean, was able to establish a much wider sphere of control, and almost immediately took advantage of his new base by attacking with carrier-borne aircraft the Italian fleet at Taranto.

It also happened that the Greeks ran rings round the Italian invaders and tossed them smartly back into Albania. But then, in the spring of 1941, a new threat appeared. Concerned with the Italian navy’s failures and the Italian army’s lack of success in North Africa, which seemed likely to impede the German war effort, Hitler despatched to their assistance units of the Luftwaffe – a very different proposition from the Italian Regia Aeronautica – and, immediately, Stuka dive bombers closed the Mediterranean to through convoys. With seaborne supplies threatened, there was a great need for land bases for aircraft and, with the threat of a German invasion of Greece through the Balkans, a British army was put ashore in that country.

One month later the long-expected German attack came via Yugoslavia, Bulgaria and Rumania. Outnumbered on the ground and in the air and deprived of supplies by the needs of North Africa, the British and the Greeks were immediately in trouble, and almost from the outset were fighting for their very survival.

Prologue

Crete lay like a basking lizard in the spring sunshine. The warm waters of the Aegean lapped at the brown rugged inlets that scarred the sides of the rocky outcrop which ran like the lizard’s scaly backbone the whole length of the island.

The slopes of the coastal plain were covered with scrub and brown grass, with here and there small areas of cultivated terraces among the olives and cypresses and the acres of flowers that softened the arid harshness of the land. Masses of small white irises and big daisies grew among the oleander, tamarisk, poppies and flowering thistles, and the valleys hid bright birds and gorgeous butterflies. It was easy to see why the land had been so beloved of Byron and Rupert Brooke.

Staring from the window of a hut beneath a tamarisk tree near Retimo, Lieutenant-Commander Henry Kennard studied the light-grey shapes of naval vessels across the harbour and the groups of men marching through the dusty sunshine, passed and re-passed by lorries towing guns or carrying ammunition along the gritty tracks. Kennard was a man in his forties, greying and with a face wrinkled like a walnut, a reservist who had served throughout the other war and had found himself recalled to fill a vital job ashore so that a younger man could go to sea. As he stared through the dusty glass, he heard the cheep-cheep of the wireless operator’s set behind him and turned.

‘Sir! Signal! It’s Loukia!’

A short square pipe sticking from his sun-reddened face like the muzzle of a gun, Kennard stood behind the operator as he wrote.

‘Loukia to Scylla. ETA 1315.’

Kennard read the signal as the operator set it down. Then, picking it up and slanting it down on to his desk, turned to the civilian sitting in a deckchair alongside.

‘Estimated time of arrival just after lunch,’ he said. ‘They’re almost there, Ponsonby.’

He glanced through the window. A destroyer group was just entering the harbour and he could see the signal flags moving up to the yard-arm in bright splashes of colour. The sun caught the glass below the bridge and picked out the smooth barrels of the guns, and he could make out white-clad men forming up on the foredeck. The ships looked sleek and deadly, but Kennard knew how vulnerable they were to German dive-bombers.

‘I think those bastards back in England have landed us properly in the dog’s dinner this time,’ he said. ‘They can’t have had the slightest idea what they’re expecting us to do, chucking the pongos into Greece like that. All that bloody talk about keeping faith. Was your office behind it?’

Ponsonby gave him a cold stare and was just about to reply when the radio cheeped again.

‘Sir! Loukia again!�

��

‘She’s not arrived, surely?’

Kennard reached for the message, read it and passed it to Ponsonby. ‘Blenheim bomber landed in sea to east. Investigating survivors.’

Ponsonby frowned. ‘They haven’t time to investigate crashing bombers,’ he said. ‘We want them in Antipalia.’

Kennard glanced quickly at him but Ponsonby was quite serious and Kennard reflected that he looked like the sort of man who took great care that his own survival was never likely to need investigation, the sort of man who would never be in a ditching Blenheim or swimming for his life to a rubber dinghy.

‘We’ll just have to wait and see,’ he said coldly.

It was a quarter of an hour before the next message came.

‘Observer and air-gunner picked up,’ Kennard read. ‘Names: PO Travers, Sergeant Kitcat. Pilot missing.’

‘Now get on your way.’ Ponsonby, who had read the message over Kennard’s shoulder, spoke quietly, urgently, as though trying by the force of his own will to drive the unseen men back to their task.

The day grew hotter as the sun moved further west, baking the dry earth on the sides of the Cretan cliffs and among the undergrowth in the inland ravines. The sky grew brassy with its heat, and, bored, Kennard went for a cup of tea to a small square white house down the road where a movement office had been set up. It boasted a kettle and an electric cooker, and had kept him in tea and gossip ever since he’d arrived. When he returned the radio was cheeping again, and the radio operator put the message into his outstretched hand without a word. ‘PO Travers died,’ he read.

‘ETA 1500.’

‘They’ve lost two hours,’ Ponsonby said.

‘They’re sailors,’ Kennard snapped angrily. ‘No sailor likes to see another man drown. It might be his turn next. Because that’s what happens, you know. They go down into the darkness, gurgling and blowing bubbles and trying to shout to their God, to their mother, to their friends, and unable to, because the salt sea water’s choking them. “Lost at sea” or “Lost with the ship” doesn’t really sum it up, you know. That’s newspaper stuff – something dreamed up by the hurrah departments – all a bit remote, even a bit romantic. Drowning’s what happens and that’s slow and agonising.’

Ponsonby stared at him coldly and Kennard knew he had no idea what he was trying to say. How could he? Probably the most dangerous thing Ponsonby had ever done was climb up the gangway of the destroyer that had brought him to Crete.

The radio cheeped again, unexpectedly, and the operator’s voice cracked. ‘Sir!’

‘Loukia?’

‘Yes, sir. Trouble.’

‘Now what, for God’s sake?’ Ponsonby’s voice was fretful and angry, as though he resented the minor incidents of the war interfering with his carefully laid plans, and they leaned over the operator’s shoulder to watch as he wrote.

‘Am being attacked by MAS boats,’ the message read and the two men behind the operator stared at each other.

‘There’s another coming, sir. “Casualties. Damage. Am attempting to reach nearest land!”’

Ponsonby turned away, his eyes angry. ‘It’s not the nearest land we want,’ he said. ‘It’s Antipalia.’

Kennard didn’t reply. This corner of the Mediterranean had become damned dangerous lately, he thought. A backwater from the mainstream of the war, it had just lately become a place where it was wiser not to linger long on a clear day. The time when the Royal Navy had lorded it over the place after the battles of Matapan and Taranto had gone.

‘Damn,’ he said quietly, his voice grieving and full of a service-man’s bitterness against those who hazarded lives for politics, and ships for victories that would count in the press at home.

‘Damn,’ he said again. ‘Damn, damn, damn!’

Part One

Defeat

One

If it hadn’t been for the shopkeeper in Heraklion on the north side of Crete, Cotton might never have been involved.

The Cretan was obviously a student of the three-card trick and switched Cotton’s coins so fast it deceived the eyes of most of the people looking on. But Cotton had seen it done before in the Portobello Road in London and, grabbing the Cretan’s hand in his big fist, he wrenched the missing coins free and jammed them into his pocket. Then, lifting the slices of melon he’d bought, he glared into the Greek’s glittering charcoal eyes, his face red and angry.

‘A’fu ’den to xri’azome,’ he snorted. ‘Oa tu to xa’riso.’ And shoved the ripe slices of melon in the Cretan’s face.

His features dripping with juice and dark with fury, the Greek reached for a knife. Cotton snatched it from him and flung it away and the two of them spat at each other in Greek until more Greeks arrived and things started to look nasty. That was when Patullo appeared.

‘You’d better hop it, Corporal,’ he said casually. ‘I’ll sort this out.’

Cotton didn’t argue. Lieutenant Leonidas John Patullo was well known aboard the six-inch cruiser Caernarvon, in which Corporal Cotton was an insignificant member of the Royal Marine detachment. Patullo was Wavy Navy, a languid ugly-handsome smiling man of enormous wealth who, despite his manner, had made his presence felt in no uncertain way, even among the stiff-necked regular denizens of the wardroom. Patullo was a flutter, an oddity. With umpteen degrees in Balkan languages, he’d been in the Piraeus, the seaport of Athens, when war had broken out in 1939, and had slipped out to Alexandria in the yacht of a wealthy Greek friend to enlist as an ordinary seaman in the navy.

He did sort out the matter of the melon and the Cretan’s face. As Cotton had expected. After all, supported by his wealth, Patullo had wandered intimately in peacetime Rumania before finding his way to Greece long before Mussolini had decided it might look better as an Italian colony. He knew Bulgaria, Yugoslavia and Greece like the back of his hand and had sailed his own boat among the Dodecanese and Cyclades Islands. But his hope of being a simple sailor had been dashed at once when someone in Alexandria had recognised him. Since everybody even then expected Mussolini to march into Greece at the first opportunity, and since nobody else spoke Greek, and – despite what they always said at home – none of the Greeks spoke English, he had been commissioned at once, posted to Caernarvon and put in charge of Intelligence.

The matter of the melon was settled within ten minutes and he caught Cotton up as he was trying to explain to his friends what had happened to the fruit he’d promised to produce.

‘Really should be more careful whom you pick on, Cotton,’ he smiled. ‘That chap had a knife.’

Cotton straightened up, every inch of him a Royal Marine, stiff in starched khaki drill. ‘Yes, sir,’ he said. ‘I took it off him.’

‘Might have been nasty, though,’ Patullo said. ‘Cretans aren’t noted for having the sweetest of dispositions and they actually enjoy being warlike. They sometimes even wear empty ammunition belts stuffed with pellets of paper just for the look of the thing, and whole families conduct vendettas for generations.’

Cotton began to see he’d probably been lucky and he stiffened again. ‘I expect I could have handled it, sir.’

Patullo looked up at Cotton’s square bulk and the blue emery paper of beard on his big chin. ‘Yes,’ he said. ‘You probably could, shouldn’t wonder.’ He paused. ‘You were pretty articulate back there, Corporal,’ he went on. ‘In Greek, too. Did you know what you were saying to that chap?’

Cotton’s face reddened. ‘Yes, sir, I did,’ he said. ‘I told him I didn’t really want his bloody melon any more so I’d make him a present of it. I did.’

‘You did indeed.’ Patullo smiled again, then he paused and stared hard at Cotton. ‘Where did you learn to speak Greek like that?’

Cotton frowned. ‘When I was a kid, sir,’ he said. ‘I lived with a Greek family. There’s a lot of Greeks round London.’ He didn’t explain that the family in question was his own and consisted of his mother, father and three adoring older sisters, Elene, Rhoda and Maria, and that if

everybody had his own, his name was not Michael Anthony Cotton, under which label he’d enlisted in the Royal Marines, but the Mihale Andoni Cotonou he’d been given at birth.

Patullo smiled again. ‘I thought you didn’t sound as though you’d learned it at night-school,’ he observed.

‘No, sir.’

‘Well, it takes all sorts.’ Patullo seemed happy to have found a fellow Greek scholar. He had never kept himself aloof from the lower deck like some of the officers and had employed his inherited self-confidence, wealth and creative power to splash on the canvas of the everyday life of Caernarvon some of the colour of his own past. ‘Lafcadio Pringle was an Irishman of Welsh descent, and he spoke Old Norse, Flemish, Tibetan, Czech and diplomatic Latin, and he ended up as a corporal of Uhlans in the Polish army. You that sort of chap?’

‘No, sir,’ Cotton said, wondering why he hadn’t kept his big mouth shut and who the hell Lafcadio Pringle was when he was at home.

It was a small incident and it had taken place in late 1940 when the Italians had first gone into Greece. Now, five months later, since he was well aware that he was blessed with nothing else beyond the Greek language in the nature of unusual gifts, Cotton suspected that it was responsible for his being present in this hut near Retimo, standing in front of a scrubbed army table covered with maps, being stared at by Patullo and two other men.

There was a pile of signal flimsies in front of them and Patullo was tapping one of them.

‘Loukia to Scylla…’ he read out. ‘…ETA 1315…’

Cotton shifted his position slightly. ‘Who’s Loukia, sir?’ he asked. ‘A young lady? It’s a young lady’s name.’

Patullo glanced at the other two men behind the table then at Cotton, his face bland and smiling. ‘Yes, it is, Cotton,’ he said. ‘A Greek young lady’s name. But, as a matter of fact, in this case, Loukia’s a motor launch. That’s why she’s sending her estimated time of arrival – at Antipalia on the mainland. Scylla’s the code name for the base here. These two gentlemen to be precise. Lieutenant-Commander Kennard and Mr Ponsonby, of the Foreign Office.’

China Seas

China Seas The Mercenaries

The Mercenaries Road To The Coast

Road To The Coast The Thirty Days War

The Thirty Days War The Old Trade of Killing

The Old Trade of Killing Ride Out The Storm

Ride Out The Storm Corporal Cotton's Little War

Corporal Cotton's Little War Fox from His Lair

Fox from His Lair Paint The Rainbow

Paint The Rainbow Flawed Banner

Flawed Banner Covenant with Death

Covenant with Death So Far From God

So Far From God The Sea Shall Not Have Them

The Sea Shall Not Have Them The Cross of Lazzaro

The Cross of Lazzaro Smiling Willie and the Tiger

Smiling Willie and the Tiger Harkaway's Sixth Column

Harkaway's Sixth Column The Sleeping Mountain

The Sleeping Mountain The Claws of Mercy

The Claws of Mercy North Strike

North Strike Picture of Defeat

Picture of Defeat Army of Shadows

Army of Shadows Right of Reply

Right of Reply Getaway

Getaway The Lonely Voyage

The Lonely Voyage Take or Destroy!

Take or Destroy! The Backpacker

The Backpacker A Funny Place to Hold a War

A Funny Place to Hold a War Swordpoint (2011)

Swordpoint (2011) A Kind of Courage

A Kind of Courage