- Home

- John Harris

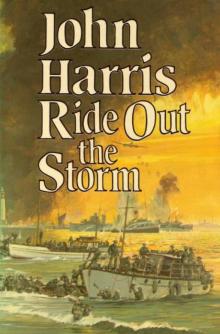

Ride Out The Storm

Ride Out The Storm Read online

Table of Contents

Copyright & Information

About the Author

Introduction

Author's Note

Sunday, 26 May

Monday, 27 May

Tuesday, 28 May

Wednesday, 29 May

Thursday, 30 May

Friday, 31 May

Saturday, 1 June

Sunday, 2 June and Afterwards

Epilogue

Synopses of John Harris Titles

Copyright & Information

Ride Out The Storm

First published in 1975

Copyright: Juliet Harris; House of Stratus 1975-2011

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

The right of John Harris to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

This edition published in 2011 by House of Stratus, an imprint of

Stratus Books Ltd., Lisandra House, Fore Street, Looe,

Cornwall, PL13 1AD, UK.

Typeset by House of Stratus.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library and the Library of Congress.

EAN ISBN Edition

0755102347 9780755102341 Print

0755127536 9780755127535 Mobi/Kindle

0755127811 9780755127818 Epub

This is a fictional work and all characters are drawn from the author's imagination.

Any resemblance or similarities to persons either living or dead are entirely coincidental.

www.houseofstratus.com

About the Author

John Harris, wrote under his own name and also the pen names of Mark Hebden and Max Hennessy.

He was born in 1916 and educated at Rotherham Grammar School before becoming a journalist on the staff of the local paper. A short period freelancing preceded World War II, during which he served as a corporal attached to the South African Air Force. Moving to the Sheffield Telegraph after the war, he also became known as an accomplished writer and cartoonist. Other 'part time' careers followed.

He started writing novels in 1951 and in 1953 had considerable success when his best-selling The Sea Shall Not Have Them was filmed. He went on to write many more war and modern adventure novels under his own name, and also some authoritative non-fiction, such as Dunkirk. Using the name Max Hennessy, he wrote some very accomplished historical fiction and as Mark Hebden, the 'Chief Inspector' Pel novels which feature a quirky Burgundian policeman.

Harris was a sailor, an airman, a journalist, a travel courier, a cartoonist and a history teacher, who also managed to squeeze in over eighty books. A master of war and crime fiction, his enduring novels are versatile and entertaining.

Introduction

We shall…ride out the storm of war and outlive the menace of tyranny… That is the resolve of HM Government… That is the will of Parliament and the nation…we shall not flag or fail… We shall fight on the seas and oceans…we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills, we shall never surrender…

Winston Churchill, 4 June, 1940

Author’s Note

Since this book is based firmly on fact, I have read everything possible on the subject by historians and by the soldiers who were there. I am particularly indebted to three books: Gun-Buster’s Return Via Dunkirk (Hodder and Stoughton, 1940), Sir Basil Bartlett’s My First War (Chatto and Windus, 1940), and David Divine’s detailed and authoritative The Nine Days of Dunkirk (Faber, 1969). I also owe a great deal to those men who agreed to go through the whole thing again with me in their homes, producing old maps and photographs and digging into their memories for modest accounts of how it had seemed to them. Like most old soldiers they were very casual about it, and for the most part seemed to consider only that it had been ‘a bit dodgy’.

Sunday, 26 May

Dunkirk!

There were nine days of Dunkirk and in the early afternoon of the first of those nine days, 26 May, 1940, well aware that his country was on the threshold of one of the greatest crises in her history, Alban Kitchener Tremenheere was walking through the flat streets of Littlehampton in Sussex towards his lodgings. He was none too sober and felt in the sort of devilish mood that had more than once in his lifetime got him into trouble. Indifferent as always to other people’s opinions, he was convinced that before long he was going to be dead, dying, or at the very least a slave of the Greater German Reich, and was therefore determined, even if no one else was, that he was going to have some fun before the chopper fell.

For eight months since the war had started the previous year there had been no fighting and, with most of the casualties coming from road accidents, he had lulled himself into believing the war wasn’t as had as people had led him to expect. He had not been alone in his view, of course, because the whole country had felt the same and even the Prime Minister had said that, like an old soldier, the war would eventually fade away to nothing as the Germans became convinced they couldn’t win.

Hitler had changed all that. With a vengeance. Invading Denmark and Norway, he had flung aside with contemptuous ease the scratch British and French force that had gone to the rescue, and then in the darkness of the morning of 10 May the blitzkrieg which had devastated Poland the previous year had begun to sweep across Holland, Belgium and Northern France against soldiers who had spent the period of the Phoney War painstakingly building up the traditional forces of 1918. By 20 May it had reached the sea to split the allied armies in two and the British, still expecting to fight according to the gentlemanly rules of earlier wars, had suddenly found themselves dealing with situations which had not even come within the scope of their imagination.

By 26 May – that Sunday morning – the disaster had reached such proportions that the Secretary of State for War had sent a telegram to Lord Gort, the commander of the British Expeditionary Force in France, announcing bluntly that there was no longer any course open to him but to fall back upon the coast. It was out of date and quite superfluous because by that time, together with the remnants of the Belgian army and the French First and Seventh Armies, the BEF was penned in a tongue of land no more than 40 miles deep and the same distance wide with, on the east, a highly dangerous indentation. Lord Gort, despite a VC, three DSOs, an MC and a Guardsman’s instinct for obedience, had decided he must disobey his French superiors’ orders to smash his way through the Germans to the armies in the south in order to close the dangerous gap opening to the east, and was in effect already doing what he was now being instructed to do.

None of these details was known to Tremenheere, of course. But, though the newspapers – making much of the self-sacrificial bombing attacks by brave young British airmen in outdated machines – would only admit that the situation was ‘grave’, it required no particular intelligence to grasp what was happening. The Channel coast of France was ablaze and the whole of the BEF, sent to the Continent with such high hopes the previous autumn, was in danger of being captured. In London, instead of being concerned with victory, thoughts were suddenly dwelling on the possibility of defeat and, though an attempt was still being made to keep open the Channel ports for the struggling army, one after the other they were falling to the Germans. Calais alone had held out – to hold the right flank of the beleaguered BEF – but by this time it was clear that when that evacuation by sea which was already uneasily being mentioned in high pla

ces became a fact, there would be only one usable port left – Dunkirk.

As he had sat on a box on the deck of the motor launch, Athelstan, on which he was employed as the hired hand, Tremenheere had stared at the heavy print of the Sunday newspapers with a sense of growing horror. He was a sturdy black-haired man whose speech still retained the burr of the Roseland peninsula south of Truro where in the last days of 1917, having got a girl into trouble, he had decided it might be a good idea to give up fishing and join the navy. By the time he found himself home again, his problem had been solved by the girl marrying the man for whom he’d worked a twenty-five-foot lugger, but his father, an unforgiving elder of the Baptist Church, had nevertheless cocked a thumb as he’d opened the door and spoken only two words in greeting – ‘Keep going’.

It hadn’t particularly worried Tremenheere because by then there had been another girl in Portsmouth and he did just what his father advised and returned to make an honest woman of her. At the age of nineteen he’d been a handsome young man with heavy brows that collided in the middle to give him the look of a good-humoured satyr; but he’d always liked his beer too much, and, three years to the day after he’d led her from the altar surrounded by none-too-sober relatives, his new wife had abandoned him like a parcel left on a bus, for a sergeant in the Royal Marines.

Despite the sergeant of Marines and the fact that he’d fought for jobs all through the thirties, Tremenheere had never once ceased to believe in the British Empire and the nobility of British arms. He’d been raised on pictures of men standing on hilltops, holding flags in heroic attitudes, and nothing had ever destroyed his faith. Now, in the general confusion of defeat and dismay, he wasn’t so sure. The headlines that morning had been like mourning bands and there had been pictures of Cabinet Ministers crossing Whitehall for Downing Street, grim-faced with a sense of destiny and despair. The reports from Germany had claimed enormous successes, and hastily drawn maps had shown a situation that was already out-of-date as events moved faster than the newspapers could co-ordinate them.

Hardly aware of the slow clang of church bells over the still air, Tremenheere had stared at the stories, sucking his empty pipe, startled at the frightening speed with which disasters seemed to be following each other. It had seemed impossible that the British Army was being defeated in France by the men they’d licked so completely only twenty years before. For months everyone had been wanting something to happen and, now that it had, events were crowding one upon another with an intensity that was terrifying. Moving restlessly on his box, he had suddenly felt badly in need of a drink. Climbing ashore from the dinghy, he’d walked to his local, aware of an uncomfortable feeling that somewhere something was terribly wrong, and as he had seen the barman waiting for his order, somehow it hadn’t seemed to be a day for a pint of mild.

‘Give us a rum, me dear,’ he’d said briskly. ‘A bloody big one!’ Now, several rums later, he was heading towards his official residence, Thirteen, Osborne Road, with a view to sleeping it off.

Number Thirteen was a small detached house that contained a kitchen-living room, a sitting room that was never used, and three bedrooms, one of which was Tremenheere’s, one his landlady’s, and one her fifteen-year-old son’s. When he arrived, his landlady, Mrs Noone, after a morning at church, was belatedly making the beds and, as the door slammed, she appeared at the top of the stairs and stared suspiciously down at Tremenheere.

‘What are you doing here?’ she demanded.

It was by no means an unusual question because during normal summers he was often away with Athelstan and they saw each other only when he appeared to bring washing and collect clean clothes. She was three years younger than he was and had been widowed since 1930, but she’d not yet lost her good looks and between them for some time had been growing an awareness of each other that had gradually become the size of a house.

He stared up at her, then he grinned and started to march up the stairs towards her. She moved back as he reached the top step. ‘What do you want?’ she demanded.

‘You know damn’ well what I want, Nellie Noone,’ he said.

‘No, I don’t.’

But she did and they both knew she did because he’d caught her eyes on him more than once, speculative and thoughtful.

‘There’s a war on, me dear,’ he pointed out. ‘And before long we’ll all be dead. So we’d be daft to waste what time we’ve got left, wouldn’t we?’

‘I don’t know what you’re talking about, I’m sure.’

But she moved back again in front of him until she was inside the bedroom.

‘We might not be allowed to, if them Nazis win,’ he pointed out.

‘Might not be allowed to what?’

‘You know damn’ well what.’

She caught the gleam in his eye and, as he made a grab for her, she shrieked and scuttled round the end of the bed. ‘You randy old donkey,’ she said.

He grinned and, jumping on the bed, boots and all, ran across it to trap her by the wardrobe.

‘You’ve been drinking.’

‘Makes a man eager.’

She pushed his hands away but, as he pulled her to the bed, her struggles grew less convincing. ‘I’ve been a widow for nine years,’ she said, her voice coming in harsh little gasps as she wriggled beneath him, her legs waving. ‘What’ll the neighbours say? What’ll happen if Teddy comes home from Sunday School?’

Tremenheere kicked the door shut. ‘That’ll stop him,’ he said.

As Alban Kitchener Tremenheere and Nell Noone happily slept off their passion clutched in each other’s arms in the afternoon sun at Littlehampton, in Dover harbour nearly a hundred miles to the east, Kenneth Harry Pepper was watching a party of naval armourers fitting an ancient Lewis gun on the stern of the naval auxiliary Daisy. Daisy had originally been a Suffolk trawler working out of Lowestoft but the coming of the petrol engine had long since swept away her sails and now, with a topped mast and a little cabin built round the wheel, she was an ugly bald-headed vessel. Because she was solid, roomy and reliable, however, she’d recently come under naval orders, her duties to carry stores, messages and personnel to more noble ships. And since it was intended that she should, if necessary, carry them as far as the Goodwins to the north where the German hit-and-run raiders sometimes struck, she’d become entitled to a gun.

The fact that the Lewis had been rejected by everyone else as useless made no difference to Kenny Pepper. It was a gun. With a gun you could shoot Germans, and it was Kenny’s dearest wish to shoot a German. He was still only fifteen and knew nothing of war beyond what he read in boys’ magazines.

‘How do you fire it, Sy?’ he asked.

Simon Brundrett, the ship’s engineer who doubled as cook, and had been considered by the navy to be the only man likely to be capable of firing the gun, pushed him away. ‘You’re too young to worry about that,’ he said. ‘You got to be a bit older for this lark.’

‘You can be too bloody old,’ Kenny said.

His eagerness to see the gun was placing him in the way of the working party, and the petty-officer in charge turned.

‘Do you mind?’ he said pointedly, and Brundrett gave Kenny a shove. ‘Go on, kid,’ he said. ‘Fuck off!’

The obscenity didn’t worry Kenny. Although he was only fifteen he heard it hundreds of times every day. Daisy’s crew were a rough lot and the Williams brothers, who ran her, a vulgar, bawdy, cheerful pair who used the word as naturally as drawing breath.

‘Fuck off yourself,’ Kenny retorted.

Brundrett scowled. ‘You shouldn’t be here. Daisy’s a naval auxiliary now and there won’t be no room for kids.’

Kenny stared about him frustratedly. Surrounded by the backdrop of the high chalk cliffs with the ancient castle nearly four hundred feet above the town, the old Cinque Port was crammed with shipping. In the main harbour there were between forty and fifty mooring buoys all occupied by ships taking on stores. Some of the ships had been damaged trying to bring soldie

rs out of Ostend, Boulogne and Calais, and workmen were already at work aboard them with acetylene welders. On one of the buoys an oil tanker was berthed; on one side of her a destroyer was refuelling while on the other was an oil-burning cross-channel steamer and several pleasure boats.

Kenny knew what was going on across the Channel. He’d even heard that the Germans would soon start erecting guns at Calais to shell Dover, and it seemed to him that it wouldn’t make much difference whether he were killed at sea or within half a mile of the shabby house he called home.

‘I’m not scared,’ he said loudly. Nor was he, because he wasn’t close enough to the hospital ship across the harbour to see the frightful work the war had done on some of the men being lifted off, and the magazines he read showed conflict only in terms of glory in which none of the heroes ever seemed to get very much hurt.

He glanced again at the ships about him, aware of anger and shame. The naval armourers had almost finished now and were applying grease to the ancient gun. Privately, they’d long since decided that, with its smooth barrel, worn breech block and battered pans, anybody who could get it to fire more than a couple of rounds without it jamming was not just a good gunner, he was a bloody miracle.

Kenny stared at them for a moment, aware of a strange excitement. To hell with Brundrett, he decided. If Daisy went out of the harbour, he was going with her.

He glanced aft. Brundrett was bent over the gun with the naval men and there was no sign of Gilbert Williams or his brother, Ernie. So, lifting the hatch of the forepeak, he dropped quickly down among the anchor chain and the new rope that was stored there, and made himself comfortable.

China Seas

China Seas The Mercenaries

The Mercenaries Road To The Coast

Road To The Coast The Thirty Days War

The Thirty Days War The Old Trade of Killing

The Old Trade of Killing Ride Out The Storm

Ride Out The Storm Corporal Cotton's Little War

Corporal Cotton's Little War Fox from His Lair

Fox from His Lair Paint The Rainbow

Paint The Rainbow Flawed Banner

Flawed Banner Covenant with Death

Covenant with Death So Far From God

So Far From God The Sea Shall Not Have Them

The Sea Shall Not Have Them The Cross of Lazzaro

The Cross of Lazzaro Smiling Willie and the Tiger

Smiling Willie and the Tiger Harkaway's Sixth Column

Harkaway's Sixth Column The Sleeping Mountain

The Sleeping Mountain The Claws of Mercy

The Claws of Mercy North Strike

North Strike Picture of Defeat

Picture of Defeat Army of Shadows

Army of Shadows Right of Reply

Right of Reply Getaway

Getaway The Lonely Voyage

The Lonely Voyage Take or Destroy!

Take or Destroy! The Backpacker

The Backpacker A Funny Place to Hold a War

A Funny Place to Hold a War Swordpoint (2011)

Swordpoint (2011) A Kind of Courage

A Kind of Courage