- Home

- John Harris

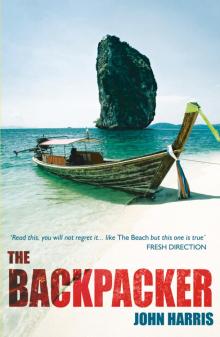

The Backpacker

The Backpacker Read online

THE BACKPACKER

JOHN HARRIS

THE BACKPACKER

First published in 2001

Reprinted 2003, 2005

This edition published 2009

Copyright © John Harris 2001

The right of John Harris to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced by any means, nor transmitted, nor translated into a machine language, without the written permission of the publishers.

Condition of Sale

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher.

Summersdale Publishers Ltd

46 West Street

Chichester

West Sussex

PO19 1RP

UK

www.summersdale.com

Printed and bound in Great Britain

eISBN: 9780857653109

Substantial discounts on bulk quantities of Summersdale books are available to corporations, professional associations and other organisations. For details contact Summersdale Publishers by telephone: +44 (0) 1243 771107, fax: +44 (0) 1243 786300 or email: [email protected].

To everyone on the 08.15 to Charing Cross.

Special thanks to Maricel Baluyut.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

1. THE END

2. THE BEGINNING

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

3. THIS IS YOUR LIFE

ONE

TWO

4. SIR RICK

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

5. THE GREAT ESCAPE

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

6. TALES FROM TWO CITIES

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

7. MCPLAN

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

8. THE WET DREAM

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

9. MARINE

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

10. ***K!

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

11. MAGNETIC NORTH

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

Author’s Note

CHAPTER 1

THE END

‘... Big Balls is number one!’ he shouted over the noise of the road. He had to shout, because even though we were riding in a Rolls Royce, the smoothest and most luxurious car on that road, it was a convertible, and even the world’s best engineers could do nothing about the sound of rubber rolling against tarmac. Nor could they redirect the air as it ricocheted off the windscreen and blasted around the ears, which, like the rest of the human anatomy, were designed in the days when aerodynamics weren’t a consideration.

‘I know he’s number one,’ I shouted, sliding forward on the back seat and resting my forearms on the leather headrest in front. His long blond hair was flying horizontally in the wind and I had to crane my neck, pushing my head between him and the driver to see his face.

‘I’m not disputing that. Big Balls is number one. Fact! What I want to know is: who was number two?’ The Triad lookalike who was driving us glanced quickly sideways at me, as though about to offer the answer to my question, before returning his gaze to the road ahead. ‘Don’t know do you? You don’t fucking remember!’ I slid noiselessly back on the animal skin and folded my arms.

‘Course I fooking do.’ He bent forward to light a cigarette in the footwell, momentarily disappearing from view, before reappearing in a mass of hairy smoke. ‘Joost give me time.’ He paused, puffing vigorously to keep the cigarette alight, and looked at his watch. ‘Fooking hell, can’t this thing go any faster? I’m gonna be late.’

‘Well it’ll be your own fault if you are,’ I said, and left a moment’s silence for my statement to sink in before turning to my girlfriend. ‘Apple, can you tell the driver to go faster, please?’

She leaned forward, one hand holding her long black hair against the wind, the other holding down her mini-skirt, and said something in Cantonese. The hum of the engine went up a pitch, throwing her back into the seat, and we rose onto the elevated carriageway into the full glare of the bright morning sunshine. Each of us turned on cue, as though attached to the same strings, and squinted at the shimmering harbour.

‘Woo-hoo!’ Rick stood up on his seat, one hand holding onto the top of the windscreen for support, sparks flying from his cigarette as the wind buffeted his face. ‘Woo-hoo! This is it John, this is the day!’

‘Wow,’ I gasped, picking up my camcorder and starting to film. ‘I’ve seen it a thousand times but it never looked like that before.’ The harbour glistened in the sunlight and I blinked against the magnified image in the viewfinder. As usual, the solitary government-sponsored junk was there, plying up and down for the benefit of tourists’ cameras, but it failed to spoil the scene. The harbour was to our right, and the shining steel and glass skyscrapers on our left. It felt like we were sitting on a speeding, metallic-blue bullet that had been fired between the two. A bullet with beige upholstery.

‘Woo-hoo! What a day it’s gonna be!’ He sat down, much to the driver’s relief, and turned to face me. ‘This is it, John,’ he said breathlessly, sweeping his hair from his face, ‘this is the day.’

I pressed the STOP button and lowered the camera. ‘Are you sure you’re doing the right thing?’

He hesitated, using one hand to shield his face from the sunlight, then nodded. ‘Yeah, the compass says so.’

Afraid to show my emotion to my best friend, I turned away from him and looked out over the other side of the flyover. Below us, in a tennis court, a perfectly synchronised group of old ladies stood on one leg as part of their morning t’ai chi class like a well-groomed flock of grey-haired flamingos. My head turned slowly, pretending to be interested in the display, as we sped past one group and then another, before they were replaced by another blinding skyscraper and I turned back.

‘You’d better have this then,’ I said, reaching into my jacket pocket and pulling out the little mahogany box. The sunlight caught its brass corners and made them wink. ‘Even though you can’t remember who was number two, I’m gonna let you have it. But don’t open it until after!’

He took it from my palm and shoo

k his head pensively. ‘It’s been a long time John.’

‘Mmm, and a long way.’

‘"To Sir William George Garthrick Jenner",’ he read from the gift label, ‘"From Lord John".’

I wasn’t born with a title, no one from south-east London ever has been, and he had never been knighted, as far as I’m aware they don’t knight ex-North Sea fishermen, but we still have them, and no one can take them away. Even though the rules that tell us whether we’ll be a worker or a player are made before we are born, some of us learn to jump from one to the other.

Nobody told me how to jump but I’m going to tell you because I’ve learned and broken free, in the same way that the other man in that car did. There is no way of telling his story without telling my own because they are the same. And if that sounds like a cliché then so be it; I don’t know how else to say it.

We had come a long way. I don’t know how many miles or countries; I lost count. It all started when I went on a three-week holiday to India.

That was four years ago...

REWIND

CHAPTER 2

THE BEGINNING

ONE

‘Beep, beep, beep, beeeep. This... is London... ’

By the time the BBC World Service intro had started its signature tune I was already standing at the bedroom window with my camcorder, finger poised over the RECORD button. I pulled aside one end of the dusty curtains and looked through the viewfinder, closing one eye and squinting the other against the bright, early morning sunshine.

It was still only one o’clock in the morning Greenwich Mean Time according to the man on the radio, which made it six o’clock in the morning, I reasoned, Indian Time. I could have been wrong, I’d had virtually no sleep all night, but even through the electronically-relayed phosphorous image in my camera it looked like early morning outside.

On the street beneath me Indians were starting their day. I let my eyes wander down the road: from the two children directly beneath my third-floor window who were mercilessly teasing a half-starved kitten, past the Sikh man meticulously polishing his rickshaw, to the point where the road curved out of sight. The narrow street looked like a perfectly-formed concrete canyon, the brilliant blue sky a snaking band above the rooftops.

‘This is Goa,’ I mumbled, ‘dum-tee dum-tee dum-tee-dum... ’

‘What are you doing John? It’s so early.’

I didn’t look around; instead ruffling the curtains and sending a small fog of dust into the air making me gag and cough slightly.

My girlfriend sighed again, more tiresomely this time. Opening my eyes and looking across at her briefly and then over to the corner of the room, I studied my surfboard, tucked into its protective travel bag. The words, Fragile! Top Load Only! written on a label and stuck on to the bag were peeling off like a wilting petal in the hot, humid air.

Sanita turned her head towards me wearily, looked at the surfboard and then back to me. ‘I don’t know why you brought that with you, I didn’t know there was any surf in India.’ She turned and rolled back onto her stomach with a huff, and buried her face in the damp pillow. I pressed the STOP button and lowered the camera. I was beginning to think she was right. Well, not beginning, I already thought she was right. Two minutes after stepping off the plane at Goa’s International Airport it was crystal clear that she was right.

The airport in Goa was a mess, a joke. The previous Monday evening at about six o’clock I had arrived on a flight from London with Sanita, my fiancée, one surfboard and minimal cabin baggage.

The first thing that hits you when you step off the plane in India is the heat. The first thing should be the smell but that has already penetrated the welded joints of the aeroplane long before the doors have even been opened. The second thing that hits you when the doors do open is the sight of what appears to be complete mayhem. Not the usual airport sight: people boarding and disembarking planes. No. What you get in Indian airports is London Underground station in rush hour meets Third World Armageddon. There were at least a dozen different modes of transport available, from clapped-out trucks to rickshaws to cow-driven baggage cars. God knows what they were all doing on the runway.

Once we’d managed to get off the plane and fight our way through to collect my surfboard we discovered that all the cash Sanita had so cleverly put into her shoulder bag, which she had equally cleverly checked in as luggage, was gone. We tried to get some help to recover the money but it was hopeless. ‘You put cash in luggage, no lock?’ said the man at the information counter wobbling his head. ‘Ohdearohdear.’ I immediately saw his point of view and told Sanita to forget it. I had a Visa card anyway – an essential part of every traveller’s kit. We picked up our gear and trudged off in search of transport into Umta Vaddo and a place to stay.

Umta Vaddo is a half-mile square area of Calangute beach that houses wall-to-wall guest houses, food-stalls and trinket shops. There’s an Umta Vaddo in every Asian town: in Calcutta it’s Sudder Street, Bangkok has Khao San Road, and Jakarta has Jalan Jaksa. All of them are different, in that it’s a different country and language, but all of them are the same: serving the same variety of backpacker food, selling the same tie-dye baggy pants, and are home to the same variety of charmless concrete guest houses. We chose the Palmtops Hotel.

I let the dusty curtains fall limply back across the window, walked across the dark room and opened the door to the small fridge, retrieving my underpants from the icebox. This I looked forward to in the morning. In anticipation I kicked the fridge door shut with my foot and steadied myself, letting out a steady puff of air. Counting to three I jumped into them, both feet at once, gasping as they came into contact with my groin. ‘Ahh, lovely.’

Sanita clucked loudly.

‘You should put your knickers in there at night,’ I said. ‘It’s brilliant.’

She sat up in bed, the damp sheet sticking to her back with sweat, and eyed me vacantly.

I don’t know how, but I knew exactly what she was about to say. Maybe it was the way her eyes dropped slightly and then came up to meet mine; maybe it was the shape of her mouth, drooping unhappily at the corners. She leaned over onto one elbow and ran a single finger between her breasts, like a windscreen wiper on a car, wiping off a layer of sweat and studying the water dripping from her finger. ‘John,’ she said, looking up at me, ‘I want to go home.’

If the airport was a joke the train station was worse. Sanita, upon seeing the mayhem, had refused to even go into the station building and had decided to wait outside. The place was full of beggars, thousands of them, in various stages of collapse and decay. I found the way in which they spotted a target, a potential source of funds, from far across the station hall and then moved in for the kill was quite amusing, and while I queued for the tickets south I had plenty of time to watch exactly how they operated.

As soon as a tourist entered the station concourse they would pounce from all four corners, steadily bearing down on their prey. It was essentially a race. It reminded me of a scene from the film Aliens. In it the creatures are steadily moving in on two of the commandos who are hemmed-in inside the ventilation ducts. The rest of the frantic crew are watching the appalling events unfold on a TV monitor which shows a dozen or so luminous green dots converging on the unlucky victims.

I watched through the fuzzy image in my camcorder as another tourist, oblivious to the impending danger, studied his guidebook for some clue as to how or where to buy the correct train ticket. The resultant look of shock on their faces was always the same: one minute they would be calmly thumbing through the pages, the next they would jump back with fright as they felt the stump of a beggar stroking their bare legs.

Amongst the beggars at the station there was a sub-group who always got to the subject first and therefore won the race. These were the skaters. Without legs, or at least without the use of their legs, they had constructed small four-wheeled trolleys, a bit like square skateboards, on which they propelled themselves along with their hands or s

tumps. While most other beggars had to be content with dragging themselves laboriously from one side of the concourse to the other, the skaters would fly across, bobbing and weaving in and out of pedestrians as they went, steel wheels screaming against the concrete floor as they shot towards the intended target.

‘Sir?’

I was so engrossed that I couldn’t place the loud knocking sound in my ears.

‘Sir? Please, sir.’

I lowered the camera and turned to face the clerk.

‘Your tickets please, sir.’ He rapped on the glass screen that separated us and pointed at the counter.

‘What?’

Sliding the two tickets under the chipped glass, he wobbled his head. ‘Two tickets. Please, sir, there are many people waiting, thank you.’

I glanced behind me at the snaking line of angry faces. ‘Oh, yeah, thanks.’ Sliding the tickets off the greasy counter I checked them, flapping the hem of my shirt with one hand to dry the sweat. The heat in the concourse was stifling, sticking my shirt to me like an extra skin. I’d drunk two bottles of water at breakfast and had mostly sweated them out already but I still needed to go to the toilet. I figured I could kill two birds with one stone: freshen up and pee.

‘Is there a toilet in here?’ I asked, turning back to the counter. The clerk, without looking up from his timetable, lazily raised an arm and pointed to the right.

Slipping the two damp tickets into my pocket, I pushed though the crowd and walked towards the corner of the building. I didn’t need a sign to know where the toilet was situated; the rank smell of sour piss and shit, and the cloud of flies hovering over a stagnant pool in the doorway were all the direction I needed. I would have turned away and waited until we were back at the guest house but I was desperate. ‘Hold your breath,’ I told myself, ‘and go in.’

As I walked towards the entrance of the toilet a small turbaned man who had been standing in the doorway moved slightly to one side, and seemed to nod to someone. He could have been dislodging a particularly annoying fly from a nostril, anything’s possible, but with the benefit of hindsight I choose to record it as a nod. Hindsight’s like that: one always remembers tiny details, even if they didn’t exist. I think the brain must invent them subconsciously to fill in the gaps.

China Seas

China Seas The Mercenaries

The Mercenaries Road To The Coast

Road To The Coast The Thirty Days War

The Thirty Days War The Old Trade of Killing

The Old Trade of Killing Ride Out The Storm

Ride Out The Storm Corporal Cotton's Little War

Corporal Cotton's Little War Fox from His Lair

Fox from His Lair Paint The Rainbow

Paint The Rainbow Flawed Banner

Flawed Banner Covenant with Death

Covenant with Death So Far From God

So Far From God The Sea Shall Not Have Them

The Sea Shall Not Have Them The Cross of Lazzaro

The Cross of Lazzaro Smiling Willie and the Tiger

Smiling Willie and the Tiger Harkaway's Sixth Column

Harkaway's Sixth Column The Sleeping Mountain

The Sleeping Mountain The Claws of Mercy

The Claws of Mercy North Strike

North Strike Picture of Defeat

Picture of Defeat Army of Shadows

Army of Shadows Right of Reply

Right of Reply Getaway

Getaway The Lonely Voyage

The Lonely Voyage Take or Destroy!

Take or Destroy! The Backpacker

The Backpacker A Funny Place to Hold a War

A Funny Place to Hold a War Swordpoint (2011)

Swordpoint (2011) A Kind of Courage

A Kind of Courage