- Home

Page 2

Page 2

China Seas

China Seas The Mercenaries

The Mercenaries Road To The Coast

Road To The Coast The Thirty Days War

The Thirty Days War The Old Trade of Killing

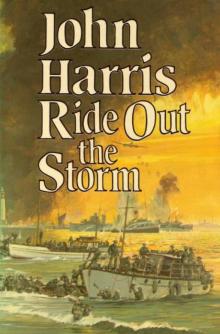

The Old Trade of Killing Ride Out The Storm

Ride Out The Storm Corporal Cotton's Little War

Corporal Cotton's Little War Fox from His Lair

Fox from His Lair Paint The Rainbow

Paint The Rainbow Flawed Banner

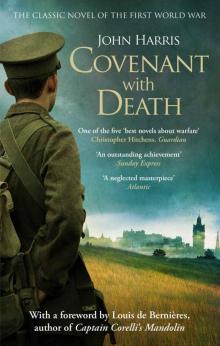

Flawed Banner Covenant with Death

Covenant with Death So Far From God

So Far From God The Sea Shall Not Have Them

The Sea Shall Not Have Them The Cross of Lazzaro

The Cross of Lazzaro Smiling Willie and the Tiger

Smiling Willie and the Tiger Harkaway's Sixth Column

Harkaway's Sixth Column The Sleeping Mountain

The Sleeping Mountain The Claws of Mercy

The Claws of Mercy North Strike

North Strike Picture of Defeat

Picture of Defeat Army of Shadows

Army of Shadows Right of Reply

Right of Reply Getaway

Getaway The Lonely Voyage

The Lonely Voyage Take or Destroy!

Take or Destroy! The Backpacker

The Backpacker A Funny Place to Hold a War

A Funny Place to Hold a War Swordpoint (2011)

Swordpoint (2011) A Kind of Courage

A Kind of Courage