- Home

- John Harris

The Backpacker Page 2

The Backpacker Read online

Page 2

Anyway, he nodded and I walked past him into the stinking concrete box. The floor was four inches deep in water, which came dribbling from a waste pipe in one corner where a man stood washing a tin bowl. I tiptoed in and turned into one of the cubicles, stopping at the entrance. There was no door, and I figured that I could probably aim the jet from three feet, thus avoiding stepping in the piles of shit that had been dropped all around the hole in the floor like bombs that had missed their intended target. I was just about to undo my zip when I felt a tap on the shoulder. I quickly pulled my hand away and turned around.

I remember gasping and sucking in a fly as soon as I saw the knife. A knife!

‘What?’

The man who held it to my chin was the same one who’d been washing the bowl. I know that because as soon as I jumped back in shock and stepped in shit he dropped the tin bowl on the floor with a loud clang. He moved forward to cover the step back that I’d just taken and pushed the six-inch blade back into my throat. I couldn’t breathe! I tried to swallow but my Adam’s apple got stuck on the knife edge. ‘Ah, ah, ah... ’

Instinctively I tilted my head up, but I could still see his face.

And I can still see it now, writing this. He had a small, almost spherically round head, like a little football. He had wispy black hair that was greased down and clung to his forehead like running ink, almost as though someone had spilt a pot of it onto his head and turned him on his side so that each run became a thick black curl. The smallness of his head was accentuated by bulbous eyes, ping-pong balls rammed into his sockets, each one blood-red from years of alcohol abuse. As he opened his mouth to speak I got a whiff of booze and saw his few rotten teeth, stained red by betel.

‘Money! Money!’ he screamed, holding out a shaking hand and tapping the fingers against the palm.

The room swam as I came to the brink of passing out. A droplet of sweat trickled backwards along my hairline before running down the back of my neck. Tilting my head higher as he pushed the blade in and looking down my nose at him, partly because my movement was restricted and partly because I was a foot taller than him, I swallowed carefully and put both hands into my shorts pockets. The money I had in them seemed to jump into my palms, and I clenched each fist and pulled them out slowly.

If anyone ever says that they were held at knife or gunpoint and refused to give up their money, they’re either crazy or it’s bullshit. The fear of the moment is so intense that it’s impossible to speak, or even move, or do anything other than what’s instructed. Even then it’s hard to move a muscle. It would be easy for me to waffle on now about how my mind was torn between giving him the cash and giving him a swift kick in the bollocks, but those thoughts only come after the event. I didn’t even register the stink of shit any more. The only reason I know I stepped in it was because it squeezed into my sandal and I found it later. My life didn’t even flash before my eyes!

What happened next is engrained on my memory.

The image of a white leg, with a leather sandal on the foot, flying through the air and striking the Indian on the side of the head is imprinted on my mind like a single frame from a film. My brain’s camera froze the picture in the split second before the foot came into contact with the side of the Indian’s head.

The poor guy didn’t know what hit him. His head went over like a boxer’s punch-ball on a spring as the foot struck his face and he was sent tumbling to one side. He was immediately followed by the body of the person attached to the leg: a mixture of tie-dye shirt and hair that went sailing past the doorway and landed with a splash on top of the Indian.

I stood, stiff and totally unmoving except for my eyes, both fists clenched in front of me, still holding out the money.

‘Go!’ ordered a voice.

‘Eh?’

He picked himself up off the Indian and grabbed my shirt collar. ‘Come on, go!’

Still incapable of making a decision I stumbled forward, dragged by the man, and splashed my way out of the room, back onto the station concourse. Only then did I hear my heart pounding as the blood rushed back into my ears and surged through my body. I opened my parched month and filled my lungs with warm air, coughing out the fly.

‘Fooking Indians!’ the man said angrily, wringing out his T-shirt. ‘Fooking India! You OK?’

‘I, um, yeah... think so.’ I blinked, and suddenly seemed to come round. ‘Yes, I-I’m OK,’ I said, unclenching my fists and staring down at the crumpled rupees.

‘Not worth being mugged for, huh?’

‘No,’ I said blankly, ‘it’s not. Thanks. I-I don’t know what... ’

‘It’s OK.’ He waved a hand through the air. ‘Listen, I’ve got to go to pick up my plane ticket. Don’t hang around in here. Follow the compass... ’

Plane ticket? This is a railway station! Compass? What compass? I was just about to ask him what he meant when he started to walk away.

‘Maybe see you later,’ he called back. ‘You’re staying at the Palmtops, right?’

I nodded vacantly.

‘Me too. Catch you there later.’

I watched the lurid orange tie-dye circle on the back of his T-shirt merge into the crowd as he jogged away and shouted, ‘What’s your name?’

But he was already gone.

TWO

When I finally got back outside to where I had left Sanita, she was gone. Shit, I thought, why does she always have to wander off at the wrong fucking time? I stood on the spot for a few minutes, perspiring and trying to steady my heartbeat. Just down the entrance steps from the station stood an ice cream vendor who’d been there when we arrived an hour earlier, and was still shouting at the top of his voice. Beside the vendor a small group of people had gathered, apparently looking at the ground. Curious, I walked over to take a look.

Sanita was sitting on the floor in the middle of the group, holding her head. She saw me and started crying.

‘What happened?’ I asked, bending down and putting my arm around her back but at the same time scanning the crowd for any sign of a tie-dye shirt.

‘John,’ she cried, sobbing harder and self-consciously pushing her skirt down below her knees, ‘I fainted.’

‘You haven’t seen a traveller around here wearing... ’

‘John!’

‘Fain– How?’

‘How’d you think?’ She glared at me, tensing her jaw to hold back the tears. ‘It’s too hot!’

Ten minutes later we were riding through the streets in a clapped-out old rickshaw, Sanita at one end of the back seat, sulking, me at the opposite end. We arrived back at the hotel but she wanted to go into the centre of town to get ‘something nice to eat’. I leaned forward and spoke though the perspex sheet that separated the driver from the passengers.

The driver looked over his shoulder briefly, told us that he knew just the place, and floored it. We sped forward with a jerk. 1... 2... 3... 4: four gears, four seconds. The handlebar clutch depressions were a blur to the human eye, the only way to detect the gear changes was from the glint of the driver’s ringed fingers in the sunshine each time he clenched and then straightened his chubby hand. Every time we cornered, one of the two rear wheels left the road momentarily and we were thrown from one side of the tin box to the other.

The driver’s view, front and rear, was almost completely blocked by trinkets, deities and other objects dangling from mirrors, and the windscreen contained a stick-on, blue-tinted sun-strip top and bottom, so that only a pillbox-sized area of clear glass could actually be seen through. He may as well have had his eyes closed.

‘How much you pay?’ the driver barked, and at the same time took a corner, leaning into the bend the way a motorcycle racer leans his bike over when cornering.

I thought quickly, calculating the distance in my mind. ‘Twenty,’ I said, leaning with him as we came out of the corner.

He shook his head. ‘No-no-no, pay twenty-five.’

‘No, it only costs–’

Sanita sighed lou

dly. ‘John, just pay the man, for Christ’s sake. Five rupees!’

I thought for a moment and then agreed, slumping back into the seat, sulking.

We screeched to a halt outside a Western-style restaurant that served, I’d learned a few days earlier, the best ice cream, milk shakes and burgers in town. Another reason for being dropped here was to change money. I had established over the past week that the best black market exchange rate for foreign currency was obtainable right outside the bookstall just up from the restaurant.

Changing money on the black market was easy and, despite the guidebook’s advice to the contrary, was not a risky business. At least ten percent could be gained over and above the current bank exchange rate by simply pretending to be interested in one of the books on sale on the bookstall next door to the restaurant. I gave Sanita my food order and walked off to pretend to buy a book.

‘Change money? Dollar, pound, yen, what you have?’

‘Pound Sterling,’ I said to the man loitering around the paperbacks. ‘Fifty.’

We haggled a little, went through the obligatory laugh at each other’s audacity routine and finally agreed a price.

The restaurant was crowded, as usual, and the air conditioning was freezing heaven. The sweat chilled and then dried, leaving my T-shirt stuck to my body. If the weather outside was ever cold the restaurant would have no business; most people would eat Indian food from the street stalls. Customers often lingered there for hours, taking outrageously small sips from their milk shakes just to stay out of the heat. It always looked like booming business, but for all I know the same people had been sitting there since breakfast-time.

Sanita had already ordered when I entered, and was sitting in one corner, idly flicking through her food tickets. She hadn’t seen me walk in so I decided to stand to one side for a while in an attempt to collect my thoughts. I was hidden from her by the few people queuing at the ice cream counter, and when they shuffled forward every time a customer was served, I ambled alongside, pretending to be interested in ice cream.

Sanita looked shattered, utterly exhausted. Her face looked pale against the brightly coloured vest she wore, and her hair, usually one of her physical charms, was hanging limply across her face, stuck to her forehead and cheeks with dried sweat.

She hadn’t even wanted to come to India in the first place, but had finally agreed just to be with me. I had convinced her by bombarding her with pictures from tourist brochures at our high street travel agent, and I think my enthusiasm eventually just wore her down and she succumbed to the unrelenting pressure.

Since arriving in Goa the previous week she had suffered from an upset stomach almost from day one, constantly needing to go to the toilet. At one point she had spent almost the whole day in the room, only leaving once to buy some medicine from a nearby chemist. Even that short errand across the street to the shop outside the hotel had turned into an ordeal, in which she rushed out fitfully into the burning midday sun, bought the goods and then ran back, sweating and clutching her stomach, to the safety of our toilet.

I had always imagined that she would feel completely at home once we arrived in India, and that all her fears would be put to the back of her mind. After all, I reasoned, she was of Indian descent. My reasoning was ridiculous. Although her parents were originally from India she had been born and bred in London, and, to make matters worse, had never even been on holiday abroad before.

The ice cream queue shortened again, and I stood still to look across at my fiancée. As the teller called out another food order number and Sanita blinked and wearily stood up to collect the food, I moved from my statuesque pose and walked over to the table and sat down.

I waited for her to return with the food and start eating, before saying, ‘I got fifty to the pound, not bad huh?’

‘Great’, she said flatly, and didn’t look up from her meal. ‘What about the train south tonight? What time do we need to be at the station?’

I hesitated, stuffing half a dozen chips into my mouth.

‘John?’

‘Bit of a problem there,’ I said, swallowing and looking nervously around for the ketchup.

‘What problem? Don’t tell me you couldn’t get the tickets... ’

‘No, I got the tickets all right. They’re just not on tonight’s train; that’s all. You saw that station San – packed out.’

She looked up, her eyes wide with alarm. ‘What then?’

I still hadn’t told her what had happened to me in the station. I don’t know why. Maybe her fainting; maybe the look on her face now, I don’t know. A wave of resentment towards Sanita suddenly washed over me. Resentment at having to explain about the tickets, resentment at her fainting, at her inability to cope with the filth. Resentment at everything. ‘All the trains are full,’ I finally said, concentrating on the ketchup to avoid her stare. ‘The next available sleeper is tomorrow night.’ I paused before dropping the bombshell. ‘They only had third-class, so I bought them.’

‘You what? Oh God, no, third-class! You’re joking?’ She put her knife and fork down on the table and sighed, rolling her head back. ‘No!’

Here we go, I thought. ‘What else was I supposed to do, San?’ I screwed the top back onto the sauce bottle. ‘So I bought two tickets to that place with the temple as well, for tomorrow morning, to kill time. We can go and see the temple in the morning, come back, pick up our gear and get the night-train south. Sorted!’ I beamed.

‘Temple! Fucking hell, John, that’s all I need!’

I’d never heard Sanita swear before, ever, and was taken aback. I looked around sheepishly to see if anyone had heard her. Indians may forgive foreigners and their strange behaviour while in India, but I knew that the sight and sound of a bare-shouldered Indian girl swearing her head off would freak them out. Nobody seemed to notice.

‘I’ve got the runs twice every ten minutes, and now I’ve got to go on a bloody four-hour train ride, probably without toilets, to look at some... Arrgh!’ She put her head in her hands. ‘Jesus, John, what were you thinking of?’

‘I thought it’d be a laugh,’ I said, shrugging innocently.

‘A laugh?’ She looked through her fingers. ‘I can’t think of anything less funny.’ Lowering her hands and placing them on her stomach, she winced and closed her eyes. ‘What about the train south? How long does it take to get to... wherever we’re going?’

I’d been dreading this question. ‘T-two days,’ I said nervously.

Silence.

‘... About.’

She opened her eyes again. ‘By two days, do you mean we leave tomorrow night and arrive the next day, or we leave tomorrow night and arrive forty-eight hours later?’

‘Yeah,’ I said, nodding.

‘Yeah what?’

‘Yeah we arrive forty-eight hours after leaving here.’ I quickly put up a reasoning hand. ‘Don’t worry, you’ll feel better tomorrow. And by the time we leave for Trivandrum tomorrow night you’ll be back to normal.’

‘You said that a week ago John.’

I leaned back in the chair, relieved at having told her. ‘We haven’t even been here a week, San. Anyway, see how you feel tomorrow. We’ll go back to the hotel now and you can have a rest. How’d that be?’

She put her head back into her hands and sat in silence for the rest of the meal, occasionally picking at the food and briefly flicking through her guidebook. I noticed that she concentrated mostly on the Getting Away section.

THREE

The next morning found me standing alone on the platform of the railway station waiting for the train to the temple. Despite my optimism Sanita had not improved overnight, and by the time I had left the room she still didn’t even want to eat breakfast. We had changed rooms and moved upmarket to a new room with air conditioning so that we could both get a decent night’s sleep, but it had done nothing to ease her stomach.

Having air conditioning in the room was all well and good while you were inside, but once you stepped ou

tside you felt twice as bad as you did when leaving a room with no air con. Air conditioning, I believed, was the reason that I was sweating so heavily now, and I silently cursed Sanita.

When the train finally pulled into the station, I jumped into the air conditioned first-class car along with two middle-aged American tourists, and settled in for the ride to the temple.

The two women sat opposite me and talked constantly during the train journey, about India and its people, analysing every single thing that passed by the train window. When they saw a village they wondered how the people in the village made a living, when they heard someone speaking Hindi at a station they talked about the spread of the English language throughout the world. At one point, when they saw a cow grazing on a rubbish tip, they even began a long discussion on the quality of beef in India – no mean feat when you consider that beef is not even eaten due to the religion.

I spoke to them only briefly and found out that they were sisters from Wyoming, and they said that I could join them in a tour of the temple if I wanted to. But I declined; my thoughts were elsewhere. I had woken early, and the rocking motion of the train was sending me into a dream-like haze. Half awake, half asleep, I began to think about the guy at the train station and the conversation, if you can call it that, that we had had the day before. ‘Follow the compass’. What the hell did that mean? Follow the compass to find what? And besides, I didn’t have a compass!

The train juddered to a halt, causing me to bang my head against the side and wake up. Blinking against the harsh sun, I looked out of the window to see if there was a station sign on the platform. Just as I pushed my face up against the glass, one of the American women pushed her head in from the other direction.

‘We’re here! Better get off, young man,’ she said.

I left the station and walked wearily down a long road to get a rickshaw ride to the temple. On the pavement about halfway along was what, at first glance, looked like a bundle of rags piled on the ground. As I drew closer I realised it was in fact an animal: a huge vulture. It stood about a metre tall, but its head was bowed and almost touched the floor, as if dead. I picked up a long stick and, standing beside it at a safe distance, gave it a prod. Its head and long spindly neck lifted slowly to eye me. Then, just as slowly, it lowered again. I repeated the move and the bird did exactly the same: up... then down... The two Americans, who had been arguing with a rickshaw driver, saw what I had found.

China Seas

China Seas The Mercenaries

The Mercenaries Road To The Coast

Road To The Coast The Thirty Days War

The Thirty Days War The Old Trade of Killing

The Old Trade of Killing Ride Out The Storm

Ride Out The Storm Corporal Cotton's Little War

Corporal Cotton's Little War Fox from His Lair

Fox from His Lair Paint The Rainbow

Paint The Rainbow Flawed Banner

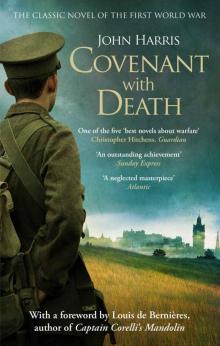

Flawed Banner Covenant with Death

Covenant with Death So Far From God

So Far From God The Sea Shall Not Have Them

The Sea Shall Not Have Them The Cross of Lazzaro

The Cross of Lazzaro Smiling Willie and the Tiger

Smiling Willie and the Tiger Harkaway's Sixth Column

Harkaway's Sixth Column The Sleeping Mountain

The Sleeping Mountain The Claws of Mercy

The Claws of Mercy North Strike

North Strike Picture of Defeat

Picture of Defeat Army of Shadows

Army of Shadows Right of Reply

Right of Reply Getaway

Getaway The Lonely Voyage

The Lonely Voyage Take or Destroy!

Take or Destroy! The Backpacker

The Backpacker A Funny Place to Hold a War

A Funny Place to Hold a War Swordpoint (2011)

Swordpoint (2011) A Kind of Courage

A Kind of Courage